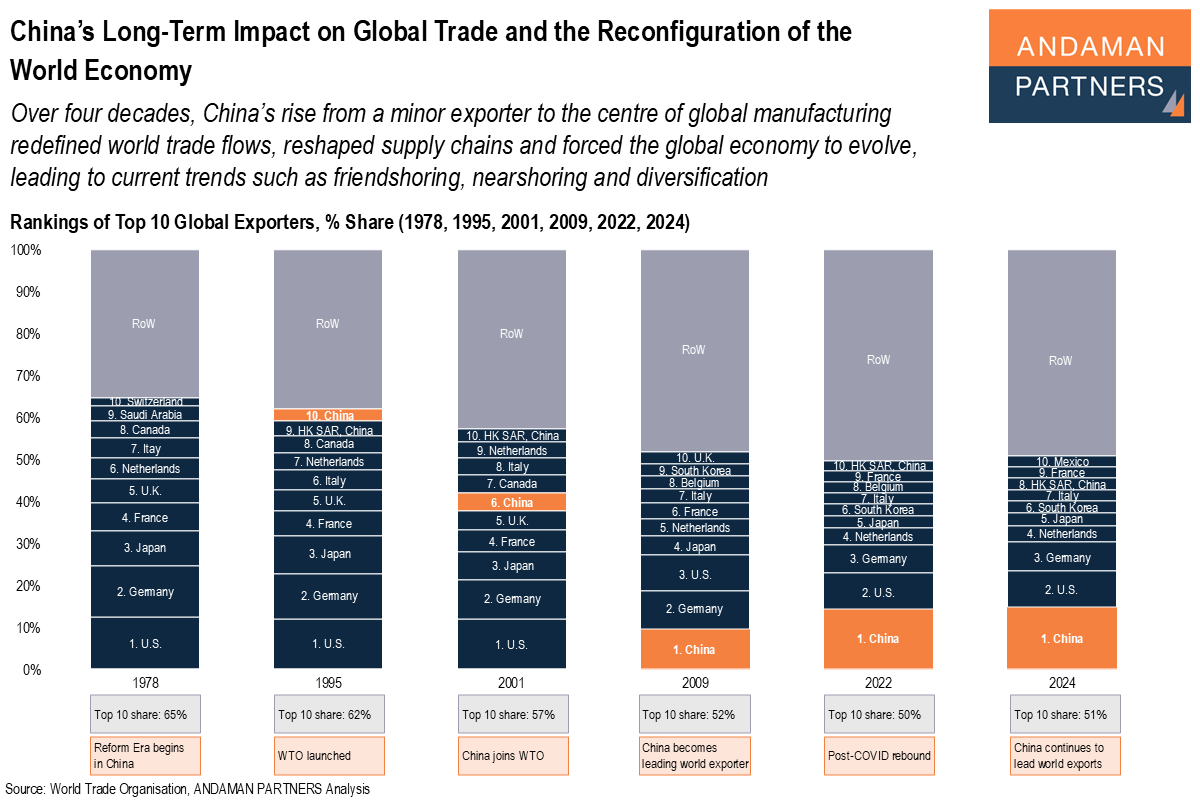

Over four decades, China’s rise from a minor exporter to the centre of global manufacturing redefined world trade flows, reshaped supply chains and forced the global economy to evolve, leading to current trends such as friendshoring, nearshoring and diversification.

Highlights:

- In the 1980s, China laid the foundations of modern trade integration by opening special economic zones, liberalising investment rules and shifting labour into export-oriented industries.

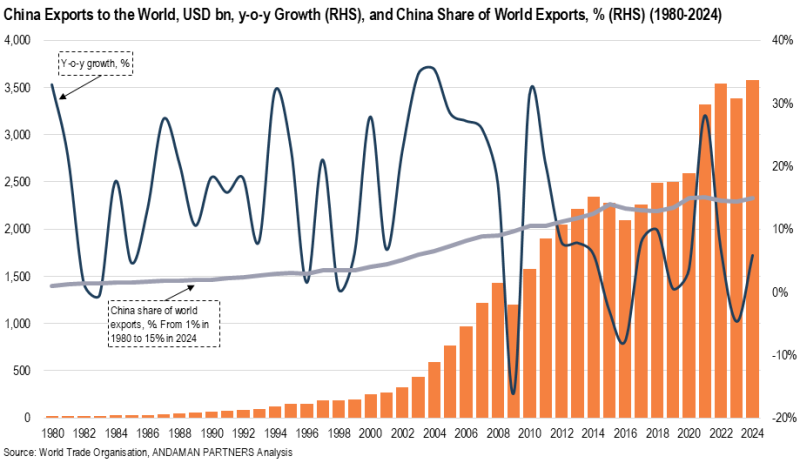

- By 2009, China overtook Germany as the world’s largest exporter. For much of the next decade, it accounted for around 15% of global exports.

- By the 2010s, China was exporting not only consumer goods but also machinery, electrical equipment, electronics, chemicals and transportation equipment.

- China’s impact on global trade extends far beyond export dominance. It is equally a story of demand creation, commodity-market transformation and the integration of global production networks around a single industrial anchor.

- Over 40 years, China has moved from the periphery to the centre of world trade, fundamentally altering global production networks and inducing the world economy’s reconfiguration toward resilience and diversification.

- The early 2020s marked the beginning of a new phase for global trade. Global companies are not retreating from globalisation; they are adapting to a world where resilience, proximity and diversification matter as much as cost.

The Global Trade System China Inherited

When China began opening its economy in 1978, the global trade system looked fundamentally different from today. Production was national, supply chains were shallow and the U.S., Western Europe and Japan dominated world trade. Emerging markets played a limited role, and China accounted for less than 1% of global exports.

Yet the reforms unleashed by China’s leadership over the following decades triggered one of the most consequential transformations in modern economic history. China did not merely participate in globalisation; it reshaped its structure, scale and logic.

Over 40 years, China has moved from the periphery to the centre of world trade, fundamentally altering global production networks and inducing the world economy’s reconfiguration toward resilience and diversification.

While China and the world changed irrevocably over this period, China remains indispensable to global trade, even as the world builds new connections around it.

The Long Arc of China’s Trade Expansion

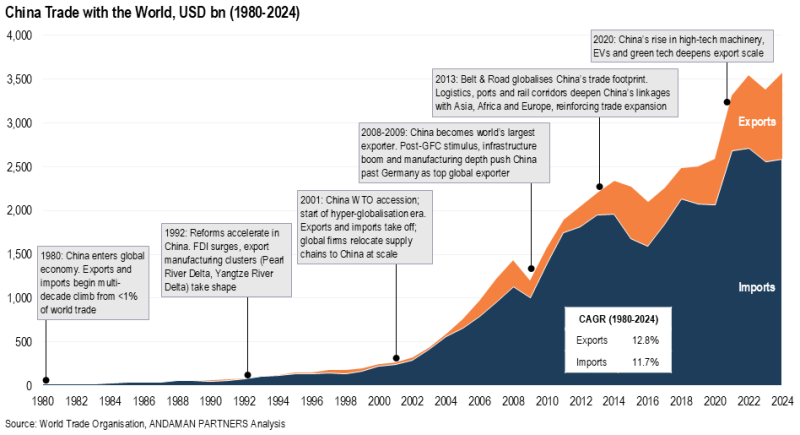

China’s total trade (exports plus imports) expanded from extremely low levels in 1980 (just over USD 18 billion) to unprecedented heights by 2024. This four-decade trajectory can be understood through several defining phases. In the 1980s, China laid the foundations of modern trade integration by opening special economic zones, liberalising investment rules and shifting labour into export-oriented industries. Although the absolute figures were still modest, the country was already developing the cost structure, labour scale and early manufacturing capabilities that would later support its rise.

The 1990s were a period of acceleration. China attracted increasing levels of foreign direct investment, and core manufacturing clusters began to take shape in Guangdong, Zhejiang, Jiangsu and the Yangtze River Delta. Global companies started relocating production to China to reduce costs and integrate into emerging Asian supply networks.

The early 2000s were transformative. China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001 provided global firms with more explicit rules, more predictable market access and a scale advantage unmatched by any other economy. Between 2001 and 2008, China’s exports expanded fivefold, and imports surged at a similar pace. By 2009, China had become the world’s largest exporter, with exports exceeding USD 1.2 trillion.

From 2009 through the 2020s, China entered a stage of increasing maturity. Stimulus-driven investment, extensive infrastructure build-out and rapid technological upgrading deepened its industrial base.

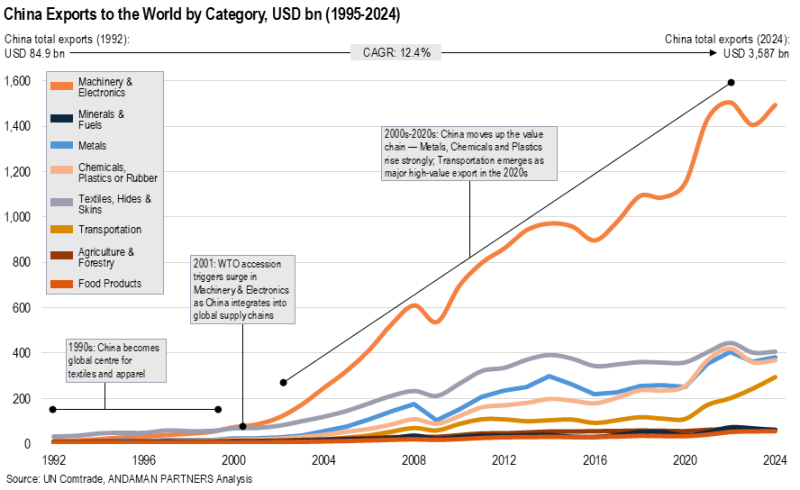

What began with labour-intensive goods gradually evolved into higher-value products as China developed a robust manufacturing base, expanded industrial clusters and fostered a broad supplier ecosystem. China developed full-spectrum manufacturing ecosystems from low-cost assembly to high-end components, capital equipment and advanced electronics.

By the 2010s, China was exporting not only consumer goods but also machinery, electrical equipment, electronics, chemicals and transportation equipment. For much of the next decade, it accounted for around 15% of global exports — the equivalent of one in every seven export dollars. This level of concentration helps explain why today’s reconfiguration trends centre on diversification: China’s scale became an asset for global growth but also a single point of dependency for many supply chains.

By 2024, China’s total trade reached historic highs, with exports exceeding USD 3.5 trillion and imports, USD 2.5 trillion.

China as a Global Buyer: The Import Side of the Story

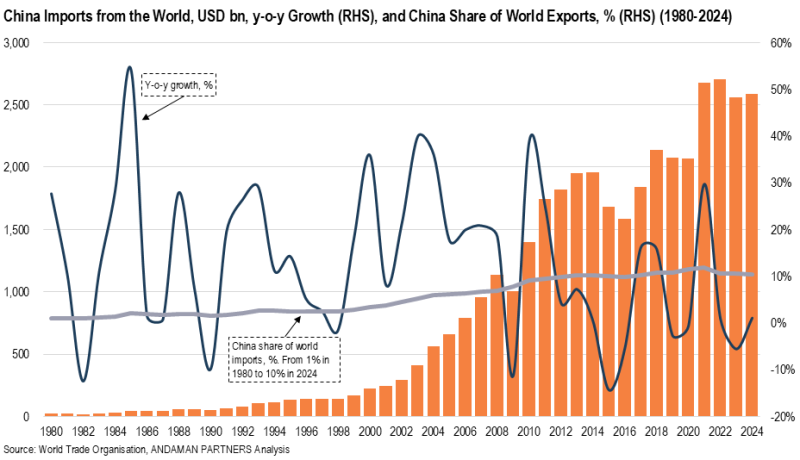

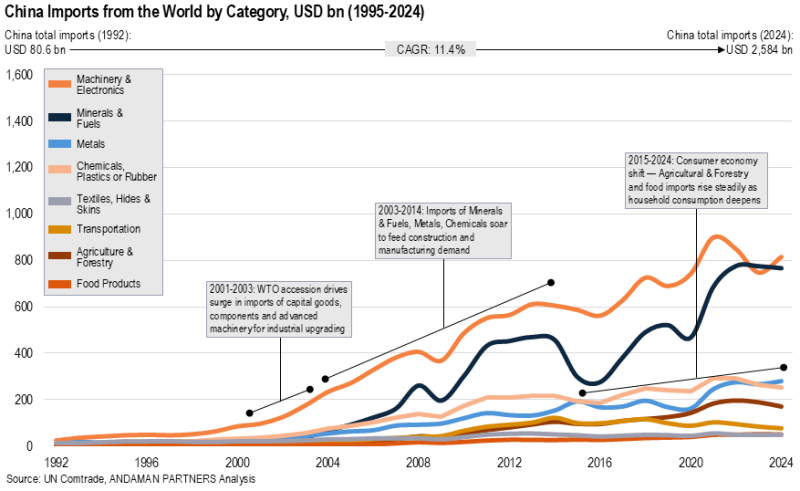

China’s integration into global trade is equally visible from the demand side. Although its exports receive more attention, China’s imports have played a central role in reshaping global commodity markets, industrial production systems and regional trade flows.

In the early stages of its development in the 1980s, China’s imports were dominated by machinery, components and industrial inputs needed for its manufacturing build-out. As industrialisation accelerated, China emerged as the world’s largest buyer of metals, energy, agricultural goods and chemical products.

During the 2003-2008 commodity cycle, China became the marginal buyer that set global prices for iron ore, copper, oil and many agricultural commodities. This demand lifted economies in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and Oceania, whose export revenues increasingly depended on Chinese consumption.

Over time, China’s import structure evolved alongside its economic transition. Growing household incomes increased demand for food, proteins and agricultural goods. The push toward higher-end manufacturing led to increased imports of components, semiconductors and advanced machinery. By the 2020s, China had become a top global importer of both raw materials and high-tech inputs, reflecting its dual role as a consumer market and a production hub.

Reordering Global Export Hierarchies

China’s ascent from 1978 to 2024 triggered vast structural realignments in global exporter rankings. Over four decades, China moved from outside the top ten into the number one position, surpassing every major industrial economy in turn. The U.S. remained a leading exporter, Germany maintained its high-tech manufacturing strength and Japan remained a core player. Yet the sheer speed and scale of China’s export growth pushed all others down the rankings.

These shifts also reflect broader changes in global supply chains. Production that once took place in Japan, South Korea, the U.S. or Europe moved to China, not just because of cost, but because China built the world’s largest, most integrated industrial ecosystem.

As China scaled up, it pulled neighbouring economies into complementary roles: Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and South Korea all became key suppliers or processors feeding into China-led value chains. The result was a regionally integrated but globally oriented production system centred on East Asia.

Sectoral Transformation: What China Trades

In exports, China’s shift from labour-intensive goods to higher-value manufacturing is clear. In the mid-1990s, textiles, apparel, toys and basic electronics dominated Chinese exports. By the 2010s and 2020s, machinery, electrical equipment, telecommunications hardware, electric vehicles (EVs), solar panels, chemicals and high-tech intermediate goods formed the backbone of export activity.

This value-chain ascent reflects China’s ability to combine scale, industrial depth, supplier density and continuous upgrading.

On the import side, structural change is also evident. In the 1990s and early 2000s, China’s industrialisation created enormous demand for raw materials. Iron ore from Australia, oil from the Middle East and Africa, soybeans from Brazil and the U.S. and copper from Chile and Peru became essential inputs for China’s expanding manufacturing base and urbanisation.

By the 2010s and 2020s, China’s imports increasingly reflected its role as a major consumer economy and a high-tech production hub. Advanced components, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, chemicals and high-end machinery became key imports. Food imports also rose sharply as consumer preferences shifted with increasing incomes.

Together, these shifts highlight the fundamental reality that China’s impact on global trade extends far beyond export dominance. It is equally a story of demand creation, commodity-market transformation and the integration of global production networks around a single industrial anchor.

Reconfiguration: 2020-2024 and Beyond

The early 2020s marked the beginning of a new phase for global trade. A convergence of structural forces shaped this period, including supply-chain risk awareness, the need for redundancy and the search for new regional production hubs. Global companies are not retreating from globalisation; they are adapting to a world where resilience, proximity and diversification matter as much as cost.

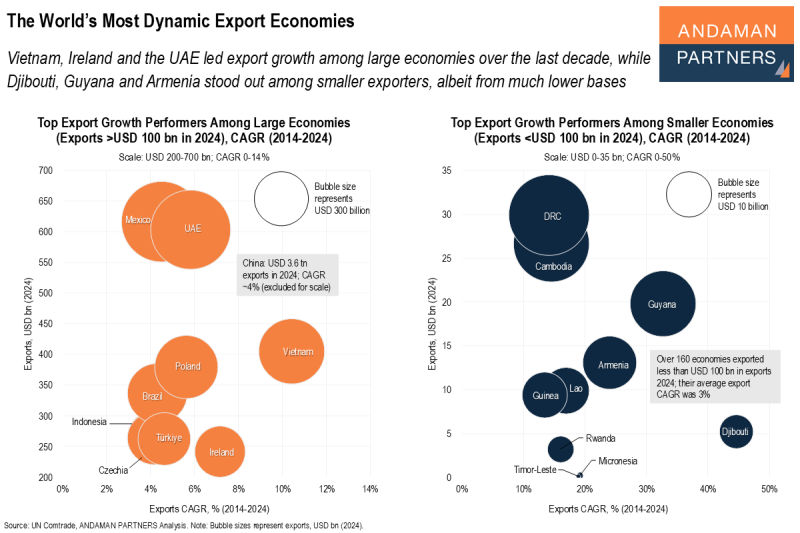

A central feature of this reconfiguration is the shift toward friendshoring, where firms establish production in countries that offer predictability, economic stability and long-term partnership potential. The U.S. strengthened manufacturing ties with Mexico and Canada; European firms deepened integration with Eastern Europe, Türkiye and North Africa; and Japan and South Korea expanded their supply networks in Southeast Asia. The objective is not to avoid China altogether but to ensure continuity by spreading risk across a wider set of partners.

In parallel, nearshoring reflects companies’ desire to shorten supply chains and improve responsiveness. Mexico has become an extension of North American manufacturing. Morocco and Türkiye have become increasingly important to Europe. Southeast Asian nations have gained from Japanese, South Korean, Chinese and Western multinationals seeking closer-to-market production bases. These shifts reflect an understanding that logistics resilience and proximity to consumers can be sources of competitive advantage just as much as cost.

Another very influential trend is China+1, which seeks to add supplementary production capacity. Firms maintain extensive operations in China but develop secondary nodes in Vietnam, India, Thailand, Indonesia, Mexico and other locations. These nodes often rely on Chinese machinery, components or capital goods, reinforcing China’s upstream role even as final stages diversify geographically. In this sense, China+1 strengthens global supply chains rather than dismantling them.

Finally, the world is gradually moving toward two-speed supply-chain ecosystems, particularly in strategic industries such as EV batteries, renewable energy, semiconductors and digital technologies. Companies increasingly operate parallel systems: one centred on China and another aligned with U.S. and EU regulatory, technological and industrial frameworks. These parallel systems are pragmatic rather than political, primarily driven by risk management, technological path dependencies and the desire to maintain access to multiple markets.

Taken together, these trends represent a rebalanced globalisation; one that retains China as a central node but distributes risk more broadly across regions and partners.

Looking Ahead: The Shape of Global Trade in the 2030s

The next decade will be shaped by three structural realities:

- China will Remain Indispensable to Global Trade:

China’s industrial scale, infrastructure, supplier networks and production efficiency cannot be replicated in the foreseeable future. China will continue to dominate intermediate goods, capital equipment and advanced manufacturing segments essential to global supply chains. - Developing and Emerging Economies will Assume Larger Roles as Complementary Manufacturing Hubs:

Southeast Asia, India, Mexico, Eastern Europe and North Africa are increasingly integrated into global value chains, offering labour pools, geographic advantages and growing industrial capabilities. These regions do not displace China but broaden the global manufacturing map. - The World is Evolving Toward a More Resilient Trade Architecture:

Globalisation is not collapsing; it is adapting to new priorities such as flexibility, proximity, diversification and technological alignment. The result is a multi-hub global economy in which China remains foundational, but not singular.

In conclusion, over forty years, China has moved from the margins of global trade to the centre. This rise reshaped industrial geography, empowered dozens of emerging economies and anchored global value chains in East Asia. Today’s reconfiguration trends, from friendshoring and nearshoring to China+1 and dual supply ecosystems, are not reversals of China’s influence but responses to it.

The world is not stepping away from China; it is building additional capacity around it to manage risk, sustain growth and enhance resilience. Global trade’s current realignment reflects not a withdrawal from China but an evolution, one in which new nodes emerge but the core remains firmly anchored.

Also by ANDAMAN PARTNERS:

ANDAMAN PARTNERS supports international business ventures and growth. We help launch global initiatives and accelerate successful expansion across borders. If your business, operations or project requires cross-border support, contact connect@andamanpartners.com.

ANDAMAN PARTNERS Wishes You a Happy and Prosperous Year of the Horse!

Compliments of the Chinese Lunar New Year to all our clients, customers, suppliers and partners.

ANDAMAN PARTNERS to Attend Investing in African Mining Indaba 2026 in Cape Town

ANDAMAN PARTNERS Co-Founders Kobus van der Wath and Rachel Wu will attend Investing in African Mining Indaba 2026 in Cape Town, South Africa.

Join ANDAMAN PARTNERS at Networking Event in Cape Town Ahead of Mining Indaba 2026

ANDAMAN PARTNERS is pleased to support and sponsor this popular Pre-Indaba event in Cape Town.

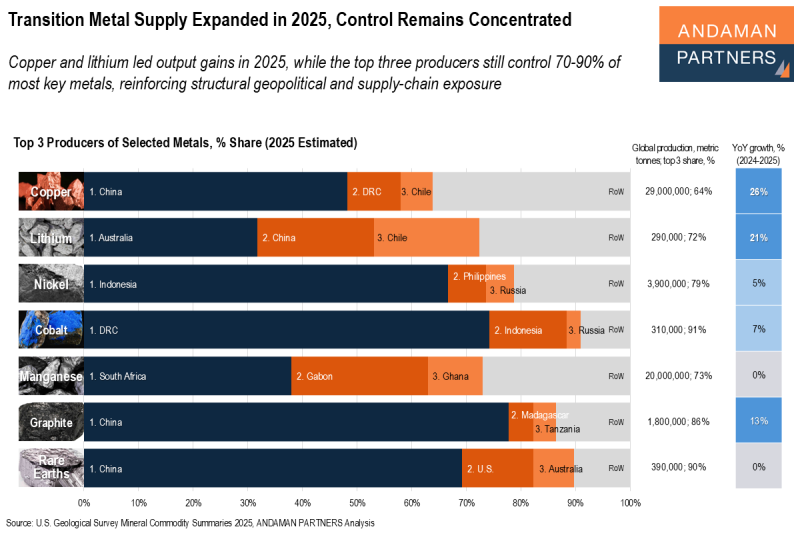

Transition Metal Supply Expanded in 2025, Control Remains Concentrated

Copper and lithium led output gains in 2025, while the top three producers still control 70-90% of most key metals.

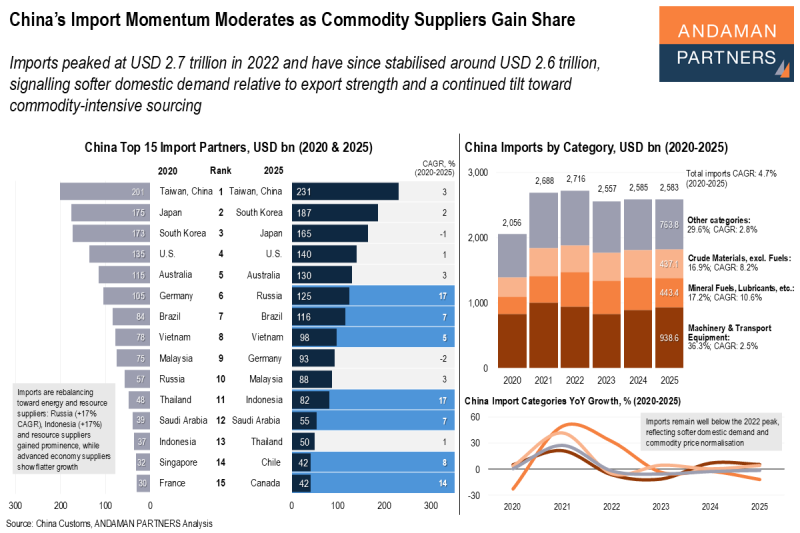

China’s Import Momentum Moderates as Commodity Suppliers Gain Share

Imports have stabilised around USD 2.6 trillion, signalling softer domestic demand and a continued tilt toward commodity-intensive sourcing.

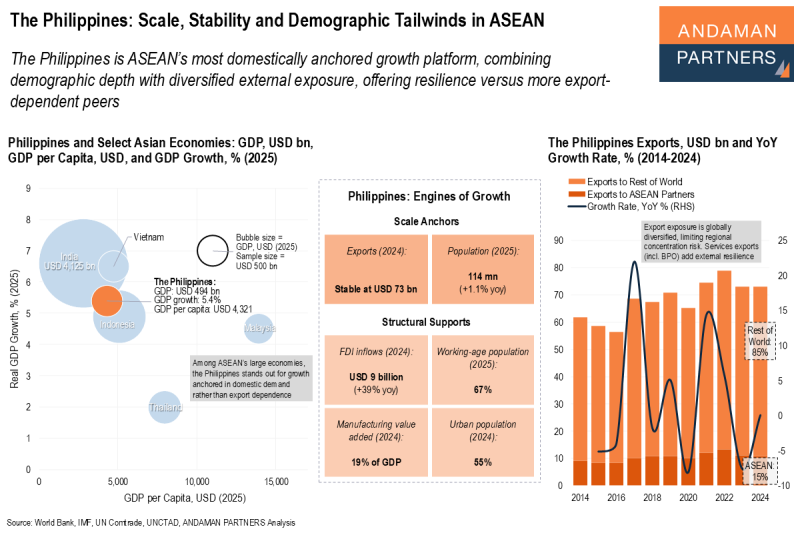

The Philippines: Scale, Stability and Demographic Tailwinds in ASEAN

The Philippines is ASEAN’s most domestically anchored growth platform, combining demographic depth with diversified external exposure.