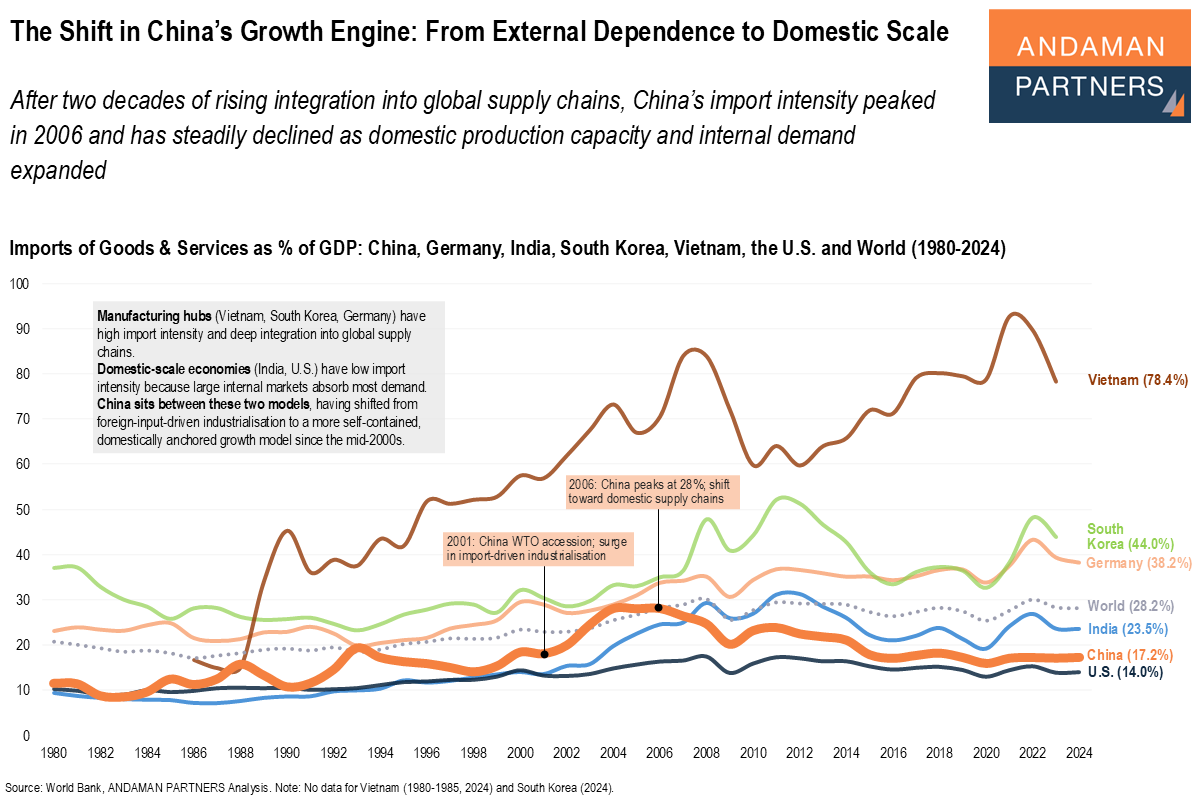

After two decades of rising integration into global supply chains, China’s import intensity peaked in 2006 and has steadily declined as domestic production capacity and internal demand expanded.

China’s long-run import intensity, measured as imports of goods and services as a share of GDP, illustrates how the country’s growth model has evolved over the past four decades. This key metric reveals the extent to which China’s economy depends on global supply chains rather than its domestic capabilities.

From the early 1980s through the mid-2000s, China’s import intensity rose steadily, peaking at 28% in 2006. This period coincided with the country’s deepening integration into global manufacturing networks, accelerated dramatically by its World Trade Organisation (WTO) accession in 2001.

In this period, China relied heavily on imported machinery, components and intermediate goods as it built out its industrial base at unprecedented speed. For global firms, this era was defined by China’s role as the world’s largest importer of manufacturing inputs and its emergence as the central assembly node in global value chains.

As with China’s overall trade-intensity pivot in the 2000s, 2006 was an inflexion point when China’s import intensity began to fall, even as its economy continued to grow, signalling a shift from an externally powered growth model to one increasingly anchored in domestic capacity. In other words, China began producing at home what it previously imported.

This reflects the rise of deep domestic supply chains, broader industrial self-sufficiency and a deliberate policy emphasis on localisation and technological upgrading. The result is an economy that is structurally much less dependent on imported inputs than it was 15-20 years ago.

For global companies, this has three profound implications:

China is no longer simply an assembly platform; it is a large, internally complete industrial ecosystem:

This reduces its exposure to foreign suppliers and gives Chinese firms the advantage of scale, proximity and integrated supply-chain depth. Competing with China in manufacturing increasingly means competing against entire domestic ecosystems, not individual firms.China’s shift toward a more self-sufficient industrial base changes the risk map for global supply chains:

Companies that once viewed China as a predictable importer of advanced components now face a competitor building those capabilities internally. As China reduces its dependence on foreign firms, these firms may become less embedded in its industrial system, potentially losing long-standing supply roles.China’s transition and its divergence with other economies are striking:

Manufacturing hubs like Vietnam and South Korea rely heavily on foreign inputs. Domestic-scale economies such as the U.S. and India depend far less on imports because internal markets primarily drive demand. China is the only economy to have moved from one model to the other within a single generation. Understanding where China sits between these models is essential for anticipating how it will behave as both a market and a competitor.

Also by ANDAMAN PARTNERS:

ANDAMAN PARTNERS supports international business ventures and growth. We help launch global initiatives and accelerate successful expansion across borders. If your business, operations or project requires cross-border support, contact connect@andamanpartners.com.

ANDAMAN PARTNERS Wishes You a Happy and Prosperous Year of the Horse!

Compliments of the Chinese Lunar New Year to all our clients, customers, suppliers and partners.

ANDAMAN PARTNERS to Attend Investing in African Mining Indaba 2026 in Cape Town

ANDAMAN PARTNERS Co-Founders Kobus van der Wath and Rachel Wu will attend Investing in African Mining Indaba 2026 in Cape Town, South Africa.

Join ANDAMAN PARTNERS at Networking Event in Cape Town Ahead of Mining Indaba 2026

ANDAMAN PARTNERS is pleased to support and sponsor this popular Pre-Indaba event in Cape Town.

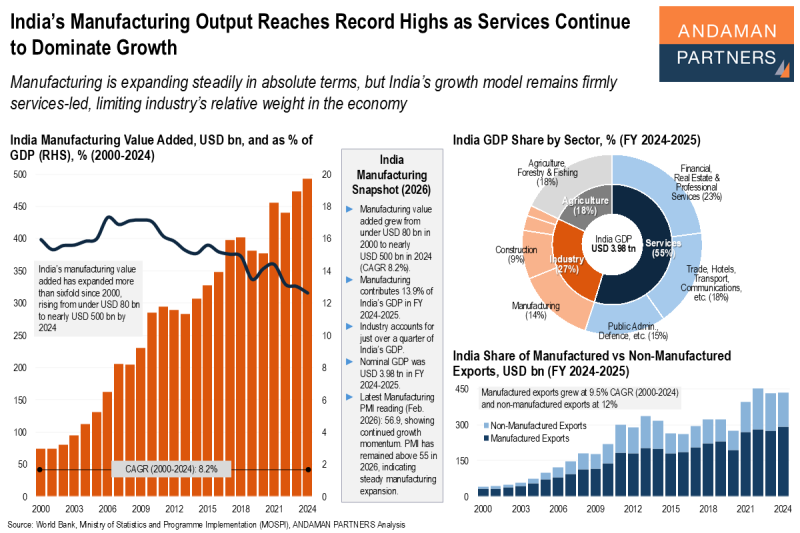

India’s Manufacturing Output Reaches Record Highs as Services Continue to Dominate Growth

Manufacturing is expanding steadily in absolute terms, but India’s growth model remains firmly services-led.

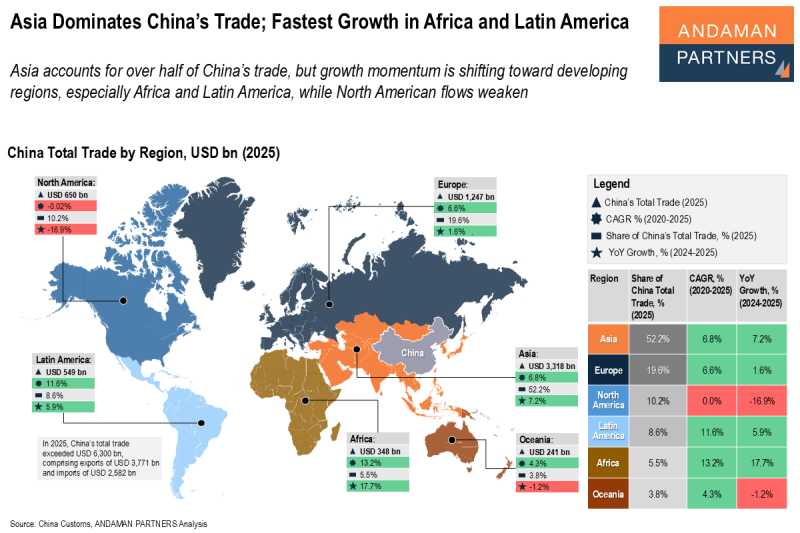

Asia Dominates China’s Trade; Fastest Growth in Africa and Latin America

Asia accounts for over half of China’s trade, but growth momentum is shifting toward developing regions, especially Africa and Latin America.

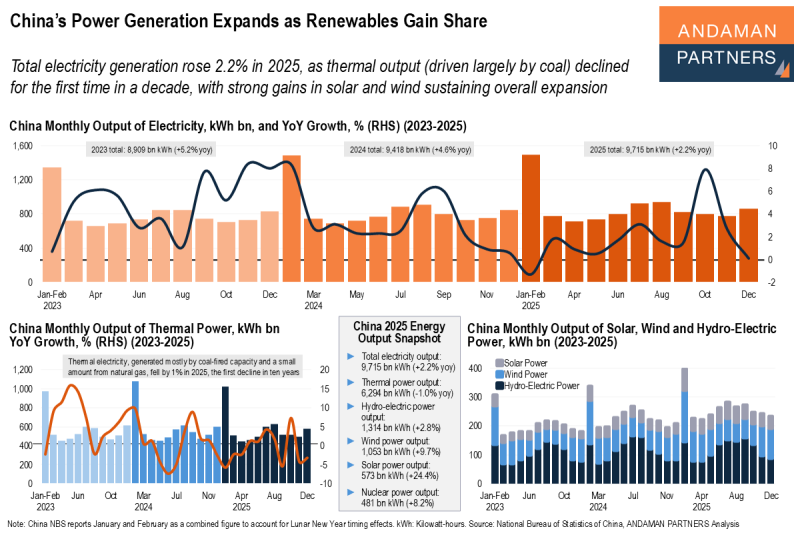

China’s Power Generation Expands as Renewables Gain Share

Electricity generation rose 2.2% in 2025, as thermal output declined for the first time in a decade, with strong gains in solar and wind.