Africa previously failed to develop a broad manufacturing base despite industrial foundations laid early in the post-colonial period. Agricultural labour increasingly flowed not into an embryonic manufacturing sector but into informal services, leaving the continent lacking the benefits of an industrial revolution. However, Africa’s potential for industrial takeoff remains, and recent advances across the continent are creating new opportunities for investors.

Highlights:

- Africa comprises 18.3% of the global population, 20% of the world’s land area and has sustained rapid economic growth over decades.

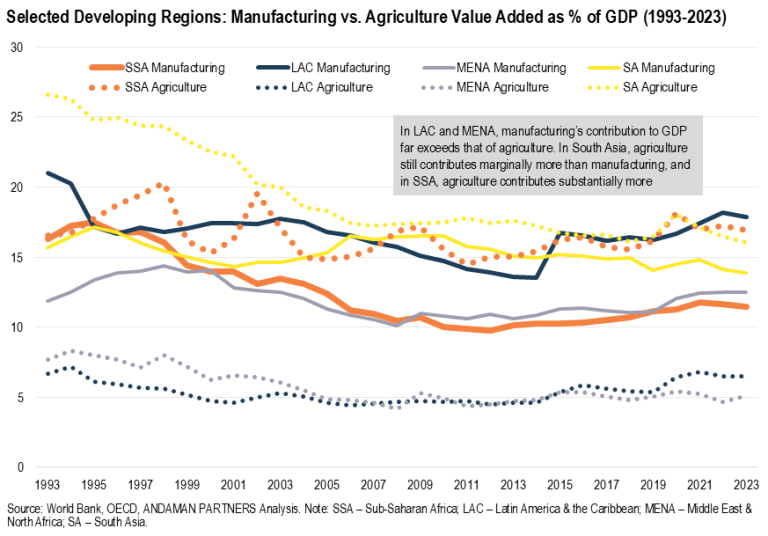

- Africa’s industrial development commenced in earnest following the end of colonialism in the 1950s but ran out of steam in the early 1970s, and agriculture still contributes significantly more to GDP than manufacturing.

- Africa’s industrial base is still comparatively tiny, accounting for only 3.2% of global GDP, 2% of manufacturing value added and 1.3% of manufacturing exports.

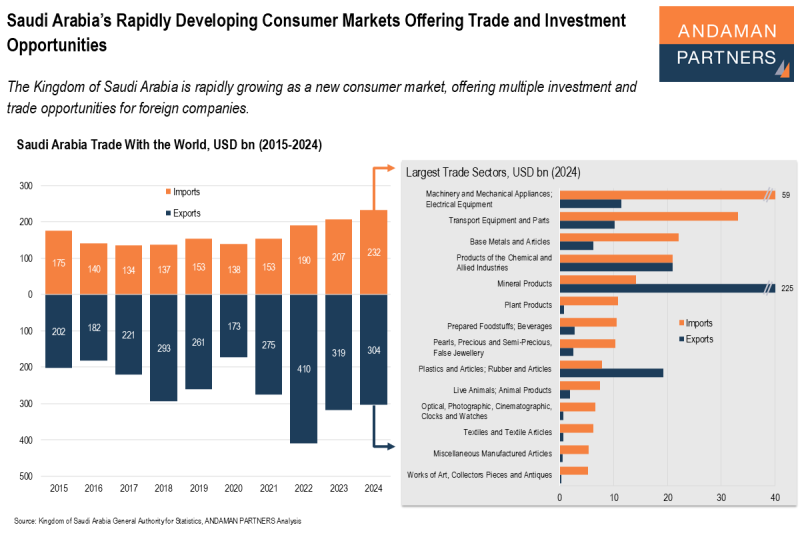

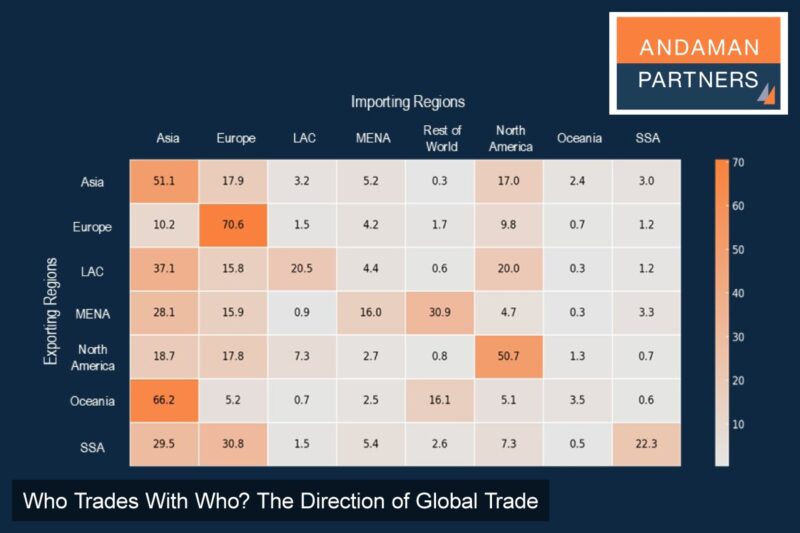

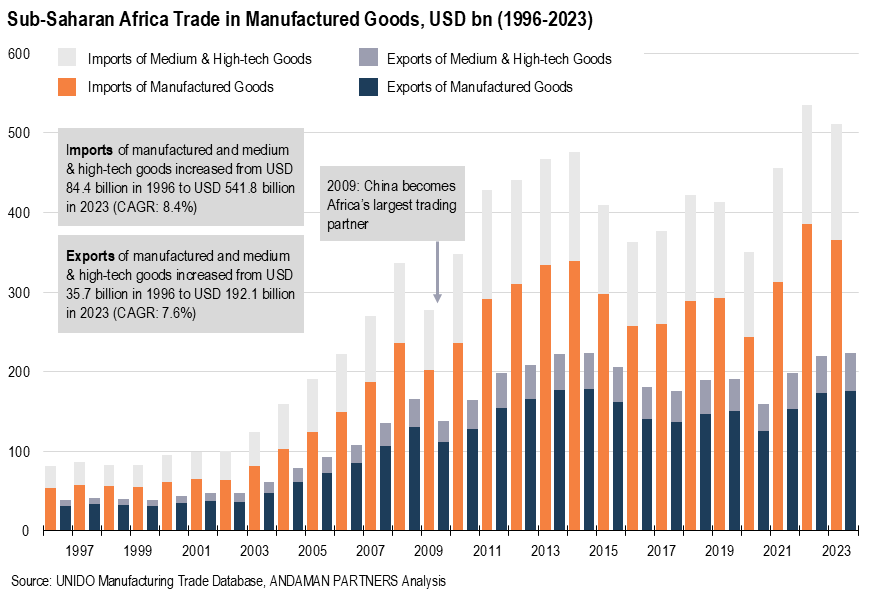

- Africa has to import the vast majority of its manufactured goods; the disparity between imports and exports expanded prodigiously from the early 2000s as the continent’s trade relationship with China started to deepen.

- Despite challenges such as a lack of infrastructure, trained staff and financial resources, several African countries are progressing with industrialisation, creating opportunities for investors.

Industrialisation is a fundamental component of economic development, with benefits such as alleviating poverty, facilitating sustained economic growth and reducing unemployment. In theory, as labour is increasingly channelled out of agriculture into more productive manufacturing, countries can systematically escape poverty and grow incomes.

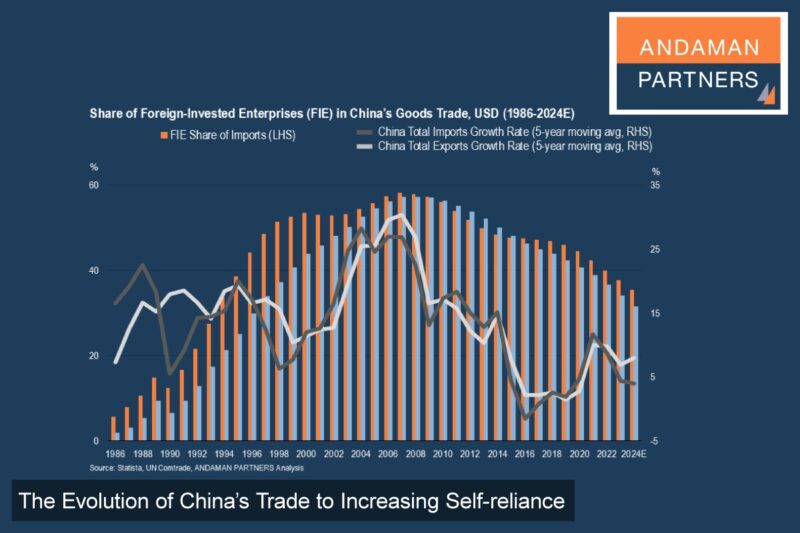

Burgeoning manufacturing sectors enabled today’s developed economies to become the world’s wealthiest nations; allowed Asian Tigers like South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan (China) to catch up with advanced economies; and made China a global manufacturing hub. Yet, industrialisation has remained unfulfilled in Africa, and in recent decades, the continent has experienced deindustrialisation, i.e., the reduction of industrial activity or capacity.

However, recent developments in manufacturing capacity in some African countries, coupled with the continent’s large and growing population and greater access to technology and capital, are creating new opportunities for investors to utilise advances in African industrialisation.

The Stalled Manufacturing Revolution

Africa comprises 18.3% of the global population and 20% of the world’s land area, and does not lack for sustained economic growth. The IMF’s April 2025 World Economic Outlook projects that real economic growth in Africa in 2026 (4.1%) will outperform the global average (3.0%) as well as Asia-Pacific (4.0%) and Southeast Asia (3.9%), while still trailing South Asia (6.0%). Since the 1980s, Africa has consistently posted some of the fastest growth rates globally, and several African countries are ranked among the world’s top 20 fastest-growing economies.

Yet Africa only accounts for 3.2% of global GDP, 2% of manufacturing value added and 1.3% of manufacturing exports. This disparity is partly attributable to much of Africa’s economic growth deriving from commodity prices, which attract investment in extractive industries rather than manufacturing.

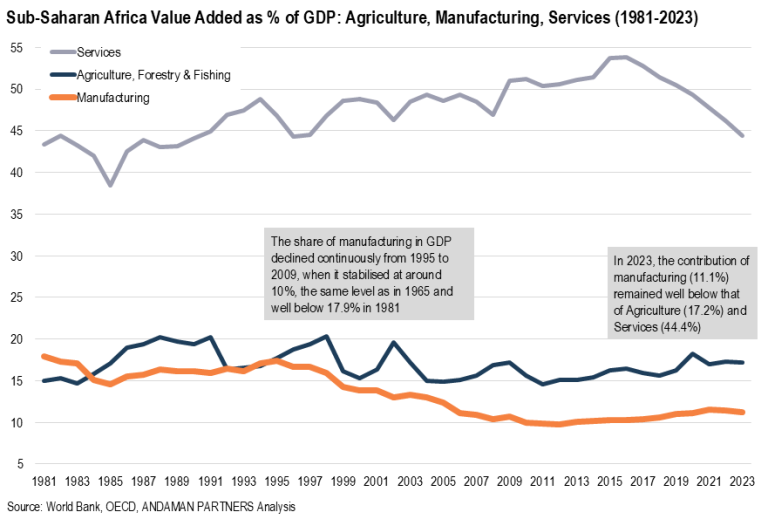

Following the independence of African countries in the 1950s and 1960s, industrialisation took off on the continent, driven by large-scale, often capital-intensive manufacturing industries owned and managed by the state. Manufacturing growth averaged 8.3% annually in Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1960s. In the 1970s, however, the boom started to fade due to a significant decline in investment productivity, shortages of imported intermediate inputs (e.g., equipment and machinery) and policies emphasising large investments over firm-level productivity. (For a more detailed discussion of African industrialisation in the post-colonial era, see Made in Africa. Learning to Compete in Industry, 2016, by Newman, C. et al.).

There was a short-lived recovery in the early 1980s when manufacturing’s share of GDP peaked at around 18%. But by this time, African manufacturing was no longer competing just with the high-wage developed economies of Western countries but with China, the inexorably rising global manufacturing hub. Since the 1980s, manufacturing’s share of GDP in Africa has remained below that of agriculture. By 2006, manufacturing’s share dropped below 12%, and it has remained below this level in the years since.

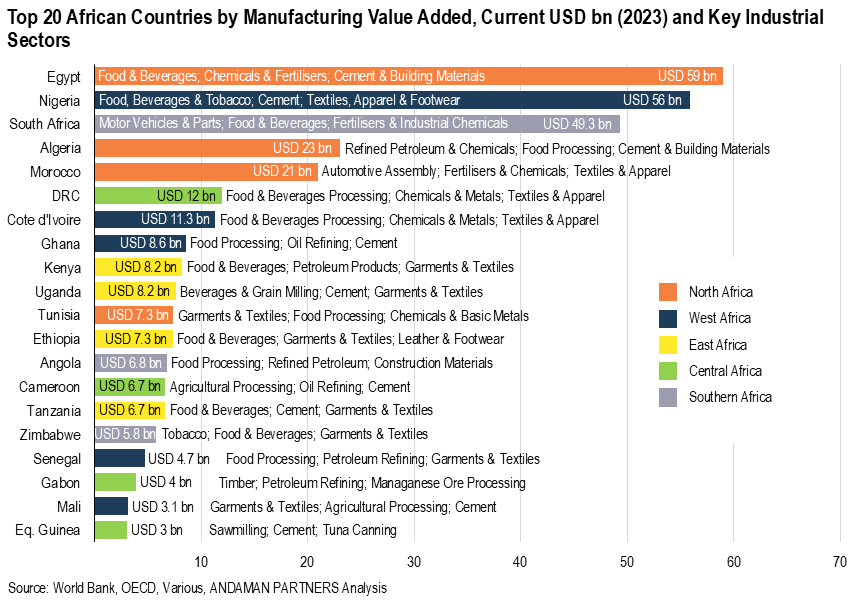

In 2023, Sub-Saharan Africa’s manufacturing output was USD 234.7 billion. This was in stark contrast to other developing regions of the world, for example, Central Europe & the Baltics (USD 368 billion), the Arab World (USD 409.2 billion), South Asia (USD 623.7 billion) and Latin America & the Caribbean (USD 1.3 trillion).

The Problematic Transition From Agriculture

The contribution of agriculture to GDP tends to decline as countries become wealthier, while the manufacturing sector’s contribution grows. Once countries attain upper-middle-income status, manufacturing tends to decline in favour of the services sector. With modern technology, high-end services (e.g., financial, software, distribution and transport) have become an engine of growth in developed economies.

In 2023, for example, the contribution of services value added to GDP was 65.4% in Latin America & the Caribbean, 65.5% in the EU and 75.4% in North America. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the figure was just over 45%, down from a high of 53.8% in 2016. This compares to 50.1% for South Asia and 51.3% for the Middle East & North Africa.

High-end services currently constitute a tiny segment of Africa’s growing service sector, which mainly comprises informal retail services. In contrast to developed economies, where high-end services were built on a burgeoning manufacturing sector, Africa did not follow the conventional pattern of shifting from agriculture to manufacturing to services.

Instead, the informal retail services sector has absorbed most of the shift from agriculture, meaning that large segments of the population failed to benefit from economic growth and increased productivity. As a result, African economies are dominated by large, low-end service sectors and mostly subsistence farming, with manufacturing mainly consisting of low-value production of products such as food, beverages, construction materials, textiles and clothing.

In developing regions aside from Africa, such as Latin America & the Caribbean and the Middle East & North Africa, the contribution of manufacturing value added to GDP greatly exceeds that of agriculture, or the gap is significantly smaller, such as in South Asia.

Because agricultural labour in Africa has not been systematically displaced to more productive manufacturing, the continent has had to import progressively more goods as its population has grown. At the same time, manufacturing capacity decreased while the remaining capacity became increasingly concentrated in low-sophistication goods.

As a result, Africa has to import the vast majority of its manufactured and medium & high-tech goods, amounting to almost USD 542 billion in 2023, while exports of manufactured and medium & high-tech goods amounted to only USD 192 billion. The disparity between imports and exports of these goods widened considerably from the early 2000s as the continent’s trade relationship with China began to deepen.

Prospects for African Manufacturing

Africa failed to achieve a sustained industrial transition from agriculture to manufacturing to services along the conventional path. Substantial progress with industrialisation in Africa is still hamstrung by a lack of infrastructure, inadequately trained and skilled workers and a lack of access to finance for people and businesses.

However, there are promising developments in various countries on the continent, albeit in the context of ongoing challenges and deficiencies. Africa has the youngest population of any continent, and by 2050, it will be the region with the world’s largest working-age population.

The African Industrialisation Index (AII), published by the African Development Bank (AfDB), tracks African progress on industrialisation. The most recent edition, published in 2022, found that a few countries on the continent have achieved sophisticated manufacturing capabilities, while several others are making steady progress toward that goal.

The top-ranked countries on the index are South Africa and three North African countries (Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia), followed by Mauritius, Eswatini, Senegal, Nigeria, Kenya and Namibia. The AfDB found that overall, many African countries made significant gains in industrial development from 2010 to 2021, with 37 out of 52 countries improving their scores.

The countries that have achieved the most rapid gains in industrial development since 2010 were Djibouti, Benin, Mozambique, Senegal, Ethiopia, Guinea, Rwanda, Tanzania, Ghana and Uganda.

Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa have well-established industrial bases. Egypt produces various manufacturing products, including textiles, fertilisers and electronics. South Africa likewise has a broad industrial base and an established automotive industry. In Nigeria, the cement industry, textiles and petrochemicals have grown substantially in recent years.

The manufacturing value added of these three largest African industrial countries, however, pales in comparison with other emerging economies such as Mexico (USD 359 billion) and Argentina (USD 105 billion), and is comparable even to the small U.S. island territory of Puerto Rico off the coast of Florida (USD 54 billion).

Algeria (refined petroleum & chemicals, food processing and building materials) and Morocco (automotive assembly, fertilisers & chemicals and textiles & apparel) have also increased manufacturing output in recent years. Beyond the top five countries, however, the rest of Africa still has relatively minor manufacturing value added, with industrial capacity mainly focused on food processing, textiles and construction materials.

Recent examples of progress in African industrialisation include a leather industry that has emerged in Ethiopia along with textiles and garments, and pharmaceuticals in Ghana and Kenya. The Kenyan government has also made substantial investments in renewable energy infrastructure, especially geothermal plants.

In Rwanda, the government has set up technology hubs and incubators to boost the country’s ICT sector, and networks of industrial parks and special economic zones have appeared in countries such as Ethiopia and Rwanda.

Along with well-established automotive industries in South Africa and Morocco, the automotive sector has expanded in several African countries, such as Ghana, where a series of assembly plants have been established since 2019.

New Opportunities Presented by African Industrialisation

Africa still has a long way to go to achieve a widespread industrial take-off. But for investors seeking to support industrialisation in Africa, the following are essential points to keep in mind when seeking out promising business opportunities:

- Look below the surface: Sectors such as food processing, textiles and renewable energy have high growth potential in Africa. Seek out rewarding investment opportunities in these sectors, focusing on market demand, competition and growth potential. Be mindful of local laws and regulations governing foreign investment.

- Go local as much as possible: Finding the right local partners will be highly beneficial, as will hiring local staff to the largest extent possible. Several service providers are now available in Africa to assist with identifying competent local partners and staff.

- Get risk management right: Carefully assess potential risks such as political instability, economic fluctuations, power supply and supply chain disruptions. Develop strategies to mitigate these risks and implement a robust supply chain strategy.

- Align with existing investment initiatives: Engage with government agencies and investment promotional bodies for support and guidance. The importance of manufacturing is articulated in the African Union’s 2011 Action Plan for the Accelerated Industrial Development of Africa and reaffirmed in Agenda 2063, adopted by the African Union in January 2015. Agenda 2063 calls on African countries to create a conducive environment for foreign investment.

- Be persistent: Investing in Africa can be fraught with risk and difficulties, but persistence (and good planning and the right partners) will eventually pay off.

ANDAMAN PARTNERS supports international business ventures and growth. We help launch global initiatives and accelerate successful expansion across borders. If your business, operations or project requires cross-border support, contact connect@andamanpartners.com

ANDAMAN PARTNERS Was a Co-Sponsor of the South African National Day Reception in Shanghai on 30 May 2025

ANDAMAN PARTNERS was a cosponsor of the South African National Day Reception in Shanghai on 30 May 2025.

Asia’s Shifting Role in Global Supply Chains — Perspectives by ANDAMAN PARTNERS Co-Founder Rachel Wu

Analysis by ANDAMAN PARTNERS Co-Founder Rachel Wu on changing patterns in global supply chains.

ANDAMAN PARTNERS Co-sponsored the West Australian Mining Club Luncheon in Perth on 27 February 2025

WA Mining Club luncheons are valuable ways to network with colleagues and clients and learn about the latest industry insights.

Africa’s Unfulfilled Manufacturing Revolution and New Opportunities of Industrialisation

Africa previously failed to develop a broad manufacturing base despite industrial foundations laid early in the post-colonial period. But Africa’s potential for industrial takeoff remains.

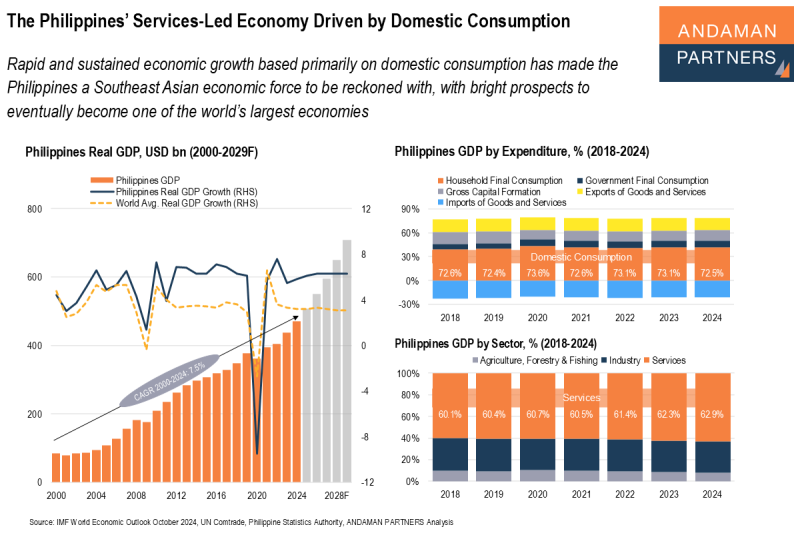

The Philippines’ Services-Led Economy Driven by Domestic Consumption

Rapid and sustained economic growth has made the Philippines a Southeast Asian economic force to be reckoned with, with bright prospects.

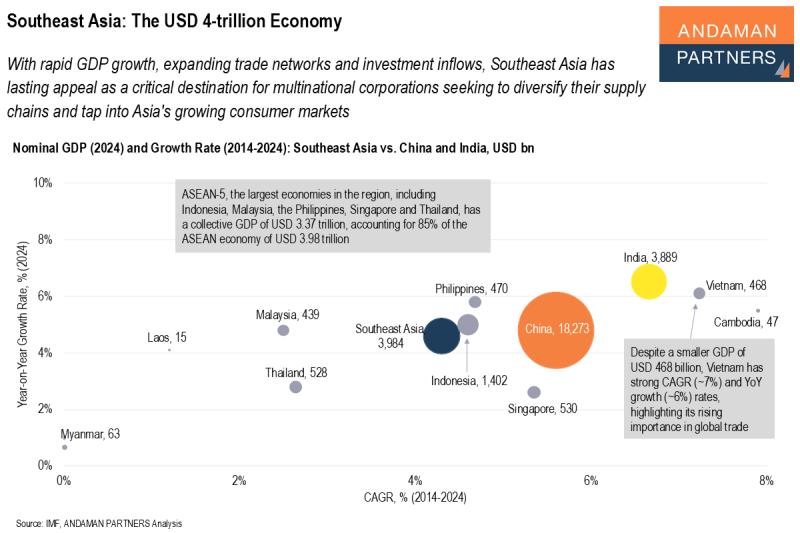

Southeast Asia: The USD 4-trillion Economy

With rapid GDP growth, expanding trade networks and investment inflows, Southeast Asia has lasting appeal as a destination for corporations seeking to diversify supply chains.